The Vietnam War, a conflict that deeply scarred the American consciousness, provoked a spectrum of domestic responses that continue to resonate through the corridors of U.S. history. This examination explores the multifaceted nature of protest during this era, revealing how media, public opinion, and cultural expressions collectively shaped the national discourse and left an indelible mark on societal norms and policies.

Origins and Escalation of Protests

The Vietnam War, unfolding amid the Cold War's tense geopolitical struggles, gradually stoked widespread domestic unrest and opposition within the United States. Early discord was primarily fueled by intellectuals, students, clergy, and certain portions of the media who questioned both the morality and the logic underpinning U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia. This disapproval soon magnified as the human and financial toll of the conflict became clearer through media reports and increasing casualty numbers.

In 1964, passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution effectively granted President Lyndon B. Johnson broad military powers in Vietnam without a formal declaration of war by Congress. This marked escalation spurred further skepticism and dissent. By 1967, numerous Americans found the war intolerable due to its devastating impact on both American soldiers and Vietnamese civilians. This public sentiment was quantified when surveys began to show less than half of U.S. citizens supported President Johnson's conduct of the war.

Campus protests emerged as pivotal arenas for the evolving anti-war sentiment. Students utilized colleges as platforms to express their opposition forcefully and visibly. The recruitment by military and defense contractors on college campuses provided focal points for staged demonstrations. On one notable occasion in 1966, a protest at the University of Wisconsin against Dow Chemical, manufacturers of napalm used in the war, escalated to a violent confrontation with police.

Media coverage also played a critical role in amplifying dissent, particularly after events like the Tet Offensive in 1968. Initially deemed a tactical loss for the Viet Cong, it dealt a severe psychological blow to the American public's perception of the war's likely success. Televised images of the Viet Cong attacking the American embassy in Saigon directly contradicted prior assurances from U.S. leaders about progress in the war efforts. This led to eroding public confidence and spurring anti-war sentiments further.

The controversial draft system, viewed by many as inequitable, further compounded public unrest. Academic deferments were retracted in 1966, drawing students more actively into anti-war movements as they directly faced the prospect of military conscription. Iconic rallying calls at demonstrations like "Hell no, we won't go!" echoed growing resentment and defiance against what was increasingly seen as an unjust war.

As resistance swelled, events became not merely localized conflicts but rather symptoms of a larger national crisis over military ethics, civil rights, and democratic governance. The revealing of the Pentagon Papers in 1971, which exposed deeper levels of governmental deception regarding military strategy and objectives in Vietnam, only deepened public dismay and propelled further dissent across various sectors of American society.

By coupling intense protests with thoughtful legal challenges and utilizing both modern media and traditional forms of demonstration, opponents of the Vietnam War demonstrated a multifaceted approach to dissent that significantly impacted public opinion and ultimately policy regarding U.S. involvement in the conflict. This multifaceted battleground shaped not only the course of the war but also the very fabric of American civil discourse during a tumultuous era.

Major Protests and Government Response

The 1967 Pentagon riot, referred to as the "Pentagon march", points to the rift between American society and its leaders during the Vietnam War era. Orchestrated by the Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, this protest followed other vocal displays of dissent around the country. On a day commencing with peaceful intent at the Lincoln Memorial, sentiments pivoted sharply as 35,000 protesters strode towards the Pentagon. This ensemble confronted a battalion of U.S. Marshals and military personnel stationed outside the nation's military headquarters.

As frustrations and heated exchanges soared, tensions broke barriers: soon fists, vegetables, and vitriol flew through the air. Government forces, unexpectedly thrust into the role of riot controllers, found themselves toe-to-toe with a populace disenchanted by a war perceived as endless and needless. The riot underscored a palpable physical manifestation of massive public disillusionment and opposition.

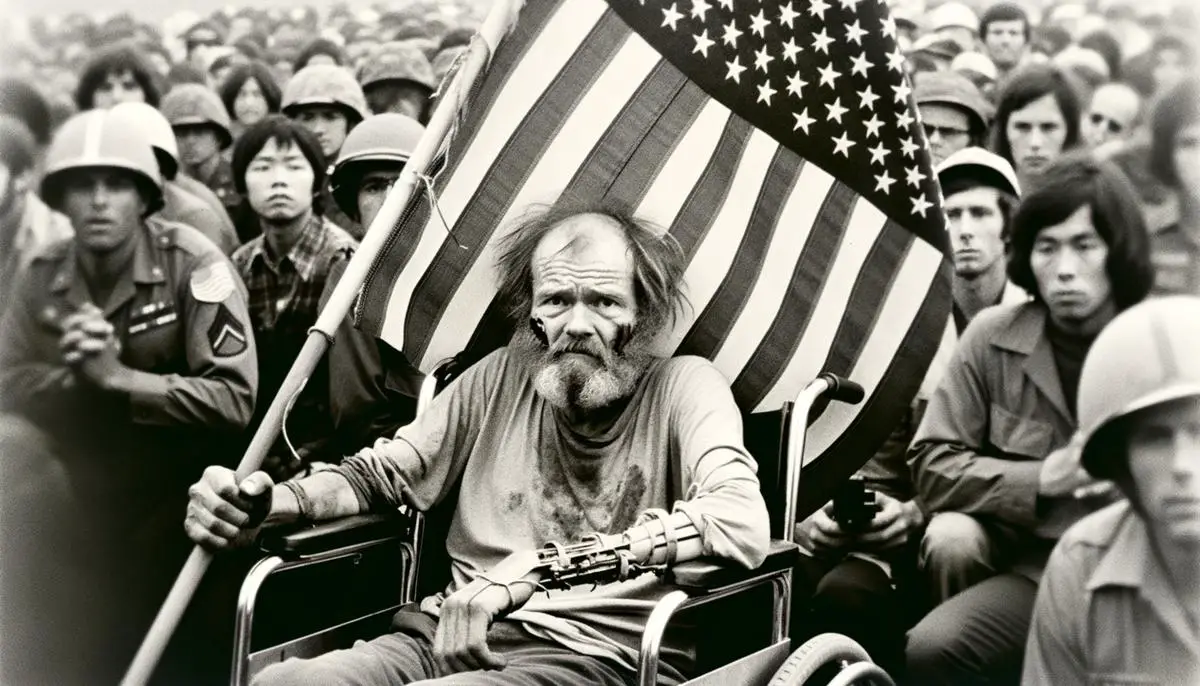

In 1971, another salient juncture, veterans exemplified by their ragged fatigues and haggard faces punctuated protests against the war they had fought. These veterans, organized into Vietnam Veterans Against the War, staged powerful and symbolic protests by incorporating elements of America's revolutionary heritage. During their "Operation POW" weekend of protest during Memorial Day, they retraced revolutionary battles and sought to parallel them against the Vietnam conflict which they claimed mirrored historic British imperialism.

These major protests triggered serious crackdowns involving heavy surveillance, mass arrests and strategic misinformation by the government, aimed at galvanizing diminishing public support for the conflict. Law enforcement frequently clashed with demonstrators, sometimes resulting in violent skirmishes.

When the leak of the Pentagon Papers in 1971 pierced through the secrecy enveloping governmental proceedings, it instigated a crucial standoff between press freedom and national security. These documents revealed the deceit practiced by successive administrations concerning U.S. strategies in Vietnam. The Nixon administration countered furiously with a fervor for injunctions aiding suppression of publication.

But this maneuver collided with the principles valued in the Constitution, most notably championed by the Supreme Court's ruling in New York Times Co. v. United States, whereby the press was safeguarded under First Amendment rights against prior restraints by the executive.

These expressions of protest and the legal maelstrom they engendered reshaped American political, legal, and social landscapes profoundly. They marked turning points guiding public consciousness towards advocacy for transparency and accountability in governance—ensuring that voices clamoring for fundamental rights amidst escalated governmental oversight were heard and made an impression upon national legislative and judicial depositories. As instruments wielded by the masses to dismantle threads of opaque administration, they emerged as cardinal points defining 20th-century American discourse on civil liberties and democratic obligations.

Impact of Media and Public Opinion

Media representations during the Vietnam War played an influential role in molding public opinion, drastically altering the trajectory of domestic support for the conflict. Televised coverage and newspaper reporting provided the American public with an unvarnished look at the realities of war, a departure from highly controlled portrayals common in earlier conflicts such as World War II. For the first time, evening news broadcasts sent graphic images of combat and its casualties into living rooms across the country, effectively shrinking the distance between the battlefield and the American psyche.

The role of television was instrumental in this dissemination of vivid wartime experiences, which often contrasted sharply with the more optimistic projections offered by government officials. With each clip of soldiers wading through rice paddies, helicopters peppered with bullet holes, and civilians caught in the crossfire, the medium etched a narrative that many felt was more authentic than the official accounts of progress and supposed imminent victory. This nightly ritual of combat footage and escalating body counts left an indelible mark on the American consciousness and swayed public sentiment to depths of skepticism and outright opposition.

The release and publication of the Pentagon Papers in 1971 further cemented this deep-seated mistrust of governmental stewardship of the war. Revealed by former military analyst Daniel Ellsberg, this top-secret Department of Defense study detailed the extent of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, dating back to the Truman administration and substantially contradicted public statements from successive presidential administrations about the state and projected course of the war. The New York Times, followed by other newspapers, published portions of these documents, embroiling the nation in a debate over the First Amendment and the public's right to know versus national security concerns.

The Supreme Court's decision to allow continued publication of these papers reaffirmed the media's role as a conduit for information and as a guardian of public knowledge and governmental accountability. This case underscored the critical function of a free press in a democratic society, particularly during periods marred by official misinformation and covert operations.

Public reaction to these media revelations was swift and profound, stoking further anti-war demonstrations and driving a wedge between government rhetoric and constituent approval. It significantly aided in fostering a more informed citizenry that was increasingly critical of the justifications given for continuing an already fractured and deadly engagement.

Social movements and protest activities flourished under these influences, as access to previously undisclosed details reassured many in their beliefs that the war was mismanaged and inherently flawed in its ethical rationale. It empowered a broader spectrum of society, including veterans returning from service, to share their first-hand refutations of official narratives, lending credibility and powerful emotive motivations to anti-war movements.

In sum, media coverage and the events following the publication of the Pentagon Papers played a monumental role in directing the national discourse on the Vietnam War. They brought the battlefield into public view with unprecedented clarity that galvanized a generation toward vocal dissent, shaping the war's historic and social legacy as one mired as much by games of obfuscation as by its physical skirmishes. Through this turbulent interchange of media, public sentiment, and political action, the Vietnam War remains a poignant chapter on the power of informed democracy and its perennial tensions with the corridors of power.

Cultural and Symbolic Expressions of Protest

Ron Kovic, a paralyzed Vietnam veteran, gripping an upside-down American flag during a 1972 protest in Miami, staged a scene of stark defiance and poignant dismay. This symbolism—the flag flown in distress—directly confronted the narrative of national pride with a powerful counter-imagery of national critique. It conveyed opposition to the war and a broader distress signal concerning the state of the Union itself in those turbulent times. Such moments drilled into the collective memory of the era, capturing the immense emotional and political charge of the anti-war movements.

Peace symbols proliferated widely during this period, with their roots deeply entwined in the lore of American and international protest cultures. The adoption of the peace sign—originally designed for the British nuclear disarmament movement—became ubiquitous across US protests against the Vietnam War. This simple yet profound emblem served as a rallying icon that distilled a complex array of emotions and ideas into a universal denotation of resistance and hopes for a harmonious future.

Similarly, slogans such as "Make Love, Not War" permeated the cultural lexicon, resonating beyond mere rallying cries to imbue everyday language and thoughts of a troubled generation. Whether stenciled on the makeshift placards at protests, scrawled across university walls, or worn on button badges on the lapels of young dissenters, these phrases served as threads that wove a collective identity among varied factions opposing the war. The slogans enchanted with their mixture of moral resolve and resonant simplicity, funneling individual and collective discontent into coherent and impactful public declarations.

Art also surged forth as a potent vehicle of protest. Musicians like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez became the minstrels of discontent, their songs voicing the deepest fears and loftiest hopes of the counterculture. Songs like Dylan's "Masters of War" and Baez's rendition of "We Shall Overcome" became anthems of the movement, performed at rallies, echoing in marches, and circulating widely, serving to galvanize and give harmony to a divisive body politic.

Visual art grafted the era's complexities onto canvas and photography. Iconic images—such as those capturing the human chain outside the Pentagon or the burned monk, Thich Quang Duc, who self-immolated on the streets of Saigon—led to macabre realizations of grief that transcended narratives accessible through conventional political discourse. These images, visceral and raw, etched into the public consciousness a vivid tableau of the war's realities.

Vietnam-era protests evolved their own aesthetic and dialect, crafting from despair a language of resistance and from activism, an art form. This cultural armament in the struggle against an increasingly unpopular war showcased a prevalent spirit of dissatisfaction and a dynamic canvas of creative expression. The various artistic and symbolic approaches perpetrated by that era's centrifuges of change redefined modes of peaceful resistance while articulating an evolving dialogue around liberty, justice, and human rights. As emblems and anthems flooded from this epoch's wellspring of activism, they heralded a transformative chapter in both America's streets and its storied timelines—an enduring blueprint for modern dissent.

Legacy and Historical Interpretation

The influence of Vietnam War protests is deeply etched into American society and remains significant in both official histories and collective memory. The cultural landscape has shifted, incorporating these protests into narratives that often question the balance between civil liberties and national security. These shifts are evident in military recruitment practices and public trust in government.

One notable legacy is the transition from a draft-based military to an all-volunteer force post-Vietnam. The end of the draft in 1973 marked a significant change in military recruitment, largely influenced by the widespread protests that highlighted inequalities and ethical issues in forced conscription. This shift altered the military's approach to securing personnel and subtly changed the socio-economic composition of the armed forces.

Public trust in government also took a definitive turn in the post-Vietnam years. The legacy of revealed deceptions, as detailed in the Pentagon Papers, instilled a lasting wariness about government transparency and integrity. This mistrust has persisted across generations, reflected in skepticism towards political narratives and a demand for greater accountability from leaders.

Academic and cultural interpretations of Vietnam War protests have evolved substantially. Contemporary scholarship acknowledges their role in democratizing dissent and reshaping national policies. Historians often recognize these movements for their contributions to broader civil rights advancements.

In popular culture, the iconography and stories of these protests have become iconic. Films, literature, and music continue to draw upon the imagery and sentiment of this era. Documentaries and historical analyses offer nuanced portrayals, aiming to capture the complex motivations and experiences of those involved.

However, some critics argue that nostalgic commemorations might overshadow the harsher realities of both the protests and the war itself. This discourse suggests an ongoing tension in historical interpretation—a balance between mythologizing and critically engaging with the past.

The legacy of Vietnam War protests continues to inform current social movements and governmental approaches. As new generations navigate their own political challenges, reflections on these protests offer both cautionary tales and models for civic engagement. Each year adds depth to their historical interpretation, ensuring that the impact of these movements is preserved and continually reassessed amid changing societal norms and challenges.

The protests against the Vietnam War challenged immediate policies and redefined American civil engagement and discourse. The legacy of these movements highlights a pivotal shift in how citizens interact with and influence their government, serving as a reminder of the power of collective action in shaping democratic societies.

- Vietnam War Protests - April 22, 2024

- US Founding Fathers - April 21, 2024

- WWII and America - April 20, 2024