Origins and Historical Context

Religious groups stepped up to meet the hunger crisis, their charitable ethos driving them to create soup kitchens and bread lines. Churches, synagogues, and various religious organizations saw it as their duty to care for the less fortunate. They offered free or low-cost meals for those who couldn't afford them. The Capuchin Services Center, for instance, began serving thousands daily right from the onset of the Depression. These faith-based centers served as sanctuaries for those hardest hit by the economic downturn.

Notorious gangster Al Capone, surprisingly, played a notable part in the inception of soup kitchens. In an effort to polish his public image, he opened one of the first such kitchens in Chicago. Here, three meals a day were served to anyone in need. Capone's kitchen became an unlikely lifeline for the hungry during those bleak times.

Government involvement in food aid started slowly. Initially, President Hoover shied away from direct relief efforts, believing in the importance of private charity. However, the overwhelming demand eventually led to federal action. President Roosevelt's New Deal saw the establishment of the Federal Surplus Relief Corporation, redirecting agricultural surpluses to the hungry. By 1933, millions of tons of food were being distributed nationwide, extending a vital helping hand to many struggling families.1

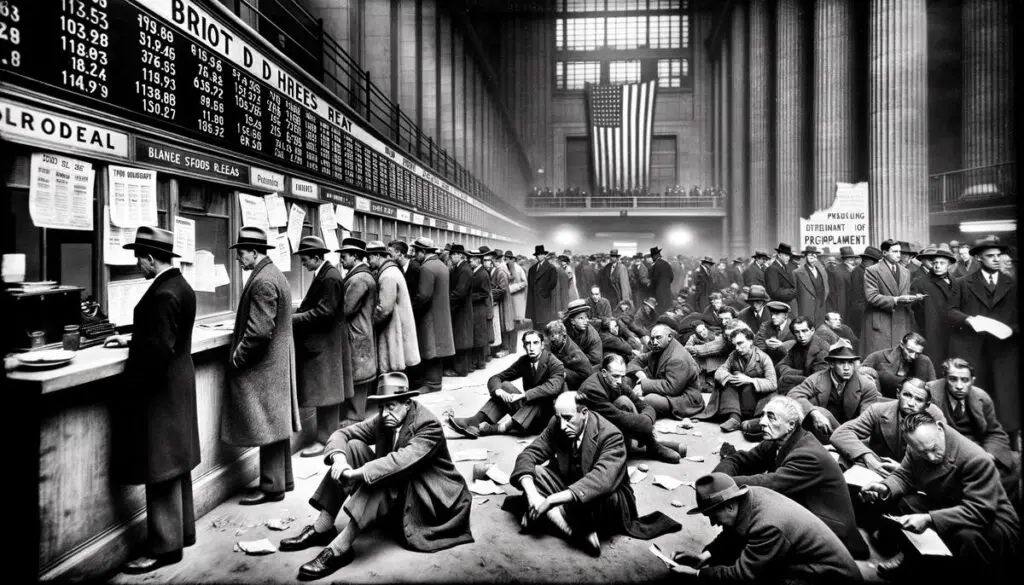

Substantial efforts were seen in urban centers like New York City, which bore the harsh brunt of the Depression. In "Hoovervilles," shantytowns where evicted families found makeshift shelter, bread lines became a symbol of both despair and survival. Soup kitchens across the city offered a taste of hope amidst widespread hunger and unemployment.

The Depression also spurred diverse forms of aid. Migrant agricultural families experienced extreme poverty, exemplified poignantly by stories like that of a West Virginia child who couldn't eat because it was her sister's turn. Makeshift meals, like Hoover Stew—a mix of macaroni, canned tomatoes, and whatever other ingredients were available—became common dishes during this time, reflecting the ingenuity and resilience of affected families.

Even today, food insecurity remains a pressing issue, with modern soup kitchens and food banks continuing the legacy of providing crucial support. Organizations like Feeding America report a steep rise in demand, reminiscent of the struggles seen during the Great Depression.2 With millions still grappling with poverty and hunger, the lessons and institutions from that era remain as relevant as ever.

Role of Religious and Charitable Organizations

Throughout history, both religious and charitable organizations have played crucial roles in addressing societal needs, particularly during times of crisis. The Great Depression was no different. These entities were often the first to respond, driven by a deep-seated sense of duty and compassion. Various religious groups perceived this dire period as a clarion call to uphold their moral and ethical responsibilities, aiming to alleviate the suffering of those most affected by the economic collapse.

Churches, synagogues, and other faith-based institutions swiftly mobilized their resources to establish and operate soup kitchens and bread lines. Their motivations were rooted in religious doctrines advocating for charitable deeds and the support of the impoverished. For instance:

- Christian teachings emphasize feeding the hungry and clothing the naked as acts of mercy

- Jewish tradition also upholds tzedakah, or charity, as a fundamental obligation

The Capuchin Services Center in Detroit serves as a compelling example of religious response. Opening its doors in November 1929, it quickly became a beacon of hope, serving between 1,500 to 3,000 people daily. The center, managed by the Capuchin friars, was driven by their commitment to Franciscan values, which emphasize aiding the poor and marginalized. This example illustrates how religious principles translated into tangible help for those grappling with hunger and despair.

Similarly, organizations like Volunteers of America played an indispensable role in establishing and maintaining soup kitchens across the United States. Grounded in the Christian mission of service and outreach, this group extended their efforts to provide meals and a sense of community and dignity to those in distress. By the mid-1930s, their involvement had expanded significantly, showcasing the power of organized charitable action in times of widespread need.

The Masbia soup kitchens in Brooklyn offer a modern-day parallel, demonstrating the sustained impact of these initiatives. Founded by Alexander Rapaport and Mordechai Mandelbaum in 2005, this network operates under the Jewish principle of caring for all humanity, irrespective of religious affiliation. Serving between 100 to 150 hot meals daily, Masbia has become a vital community resource. Its inclusive approach and adherence to kashrut make it a unique example of how religious motivation can drive effective charitable initiatives.3

The Great Depression also spurred secular charitable organizations into action. For instance, the American Red Cross, already known for its disaster relief efforts, stepped up to provide food and essential supplies to millions of Americans. Their extensive network and organizational capacity enabled them to act swiftly and effectively, complementing the efforts of religious groups.

As these examples show, the involvement of religious and charitable organizations in setting up and managing bread lines and soup kitchens was driven by a multitude of motivations, from genuine altruism to public relations. Regardless of intent, the outcome was a widespread network of support that provided critical aid to countless individuals and families. This legacy endures today, with modern organizations continuing to draw inspiration from the compassionate actions and resilient spirit of their predecessors, ensuring that the fight against hunger remains a priority in times of need.

Government Involvement and Evolution

Initially, government involvement in addressing the hunger crisis during the Great Depression was limited. President Herbert Hoover, adhering firmly to the belief that private charity should lead the relief effort, was reluctant to authorize federal assistance. However, the sheer scale of nationwide hunger soon made it clear that private initiatives, no matter how well-intentioned, were insufficient to meet the overwhelming need.

The turning point came with the election of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932 and the subsequent implementation of the New Deal. Roosevelt's administration recognized that coordinated, federally driven efforts were essential. In 1933, the Federal Surplus Relief Corporation (FSRC) was established as part of this broader strategy to combat the devastating effects of the Depression. This program was designed to repurpose surplus agricultural commodities, which were driving down market prices, to feed the hungry. By redirecting excess products like pork, butter, potatoes, and beans to those in need, the FSRC supported farmers and provided essential nutrition to struggling families.4

The FSRC later evolved into the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), expanding its scope to include various forms of direct aid. Between 1933 and 1935, millions of tons of food were distributed nationwide, significantly bolstering the efforts of local relief organizations. In states like Michigan, this translated to the reception of 15 million pounds of essential food items. Stories from the era highlight the emotional and practical impact of these distributions, with recipients often moved to tears upon receiving the much-needed goods.

This governmental pivot marked a profound shift in public policy, acknowledging that in times of extreme economic distress, federal intervention was necessary to ensure widespread relief. One striking account describes the delivery of surplus salt pork to a distressed community:

Many, especially the elderly who had not tasted meat for months, were overwhelmed with gratitude.

These acts of federal assistance provided more than just sustenance; they offered a semblance of hope and dignity during an otherwise bleak period.

The legacy of these early government programs can be seen in contemporary food assistance initiatives. The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP), a modern incarnation of these efforts, operates under the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). TEFAP provides food commodities to states, which, in turn, distribute them to local agencies such as food banks and soup kitchens. This program ensures that those in need continue to have access to nutritious food, building on the foundational work started during the Great Depression.

Further, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as "food stamps," offers another layer of support. This program allows low-income individuals and families to purchase food, providing immediate relief and stimulating local economies. SNAP, alongside the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), underscores the evolution of government food aid. These initiatives aim to provide comprehensive support, addressing immediate hunger and long-term nutritional needs.

The establishment of government-run soup kitchens and food assistance programs was a critical development in the fight against hunger. These initiatives have evolved significantly over the decades, continually adapting to meet the changing needs of the population. From the Federal Surplus Relief Corporation to TEFAP and SNAP, these programs collectively represent a long-standing commitment to ensuring that all citizens have access to nutritious food, particularly during times of crisis.

Today's food insecurity, exacerbated by economic downturns and public health crises, highlights the ongoing relevance of these programs. As America grapples with new challenges, the principles and structures established during the Great Depression remain vital, demonstrating that a blend of government intervention and community action is essential to addressing widespread hunger and ensuring the well-being of all.

Modern-Day Soup Kitchens and Food Banks

Today's soup kitchens and food banks have evolved significantly from their historical counterparts, adapting to contemporary circumstances while continuing to serve those in need. These modern-day institutions play a crucial role in addressing food insecurity, a problem that remains alarmingly prevalent despite economic advancements.

The Soup Kitchen in Boynton Beach, Florida, serves as a notable example of a modern soup kitchen. Starting from humble beginnings in 1983, it has grown into a multifaceted operation serving hot meals, distributing food bags, and offering various support services such as clothing donations and educational programs. The organization operates 365 days a year, serving approximately 800 meals per day and distributing over 500 food bags daily.

Similarly, Masbia in Brooklyn represents a model of modern efficiency and compassion. Founded in 2005 by Alexander Rapaport and Mordechai Mandelbaum, Masbia exemplifies how cultural and religious principles can guide effective charitable action. Operating three locations in New York City's boroughs, including a flagship in Boro Park, Masbia serves between 100 and 150 hot meals daily. Despite being a kosher kitchen, Masbia welcomes individuals of all backgrounds, embodying a spirit of inclusivity and humanity while adhering to specific religious dietary laws.

These organizations have faced unique challenges in recent years, notably exacerbated by economic downturns and the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic caused a spike in demand for food assistance, with millions of newly unemployed Americans turning to soup kitchens and food banks. Feeding America, a nationwide network of food banks, reported an 83 percent increase in people needing help since the pandemic began.1

The dramatic increase in demand highlighted several systemic issues. Supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic made it challenging for these organizations to procure enough food. Volunteer shortages due to health concerns meant that many operations had to find new ways to staff their services. The need for social distancing and other safety protocols necessitated changes in how food was distributed, shifting from communal dining settings to take-away meals and contactless delivery systems.

Despite these obstacles, many soup kitchens and food banks have managed to adapt and even thrive under pressure. The use of technology, such as Masbia's adoption of the Plentiful app for scheduling bread line visits, has improved efficiency and reduced the stigma associated with seeking help. This digital system provides a more dignified way for people to access essential food items without the humiliation of standing in long, visible queues.

Local community support has also been invaluable. In Boynton Beach, local businesses and residents have consistently rallied behind The Soup Kitchen, providing necessary donations and volunteer hours. This robust community involvement underscores the importance of local engagement in maintaining and expanding the reach of food assistance programs.

These organizations have diversified their services to address broader aspects of poverty. In addition to providing food, they often distribute clothing, toiletries, and other essentials. Educational programs, like The Soup Kitchen's "Taking Care of our Babies," aim to empower individuals with knowledge and skills that can help lift them out of poverty. Special initiatives during holidays, such as Masbia's holiday meals and The Soup Kitchen's Thanksgiving turkey distributions, bring a sense of normalcy and joy to struggling families.

The resilience and adaptability of modern soup kitchens and food banks underscore their critical role in society. However, they also illuminate the ongoing issue of food insecurity that persists even in prosperous nations. The economic crises of the past years have shown that despite advances in policy and social safety nets, there remains a significant portion of the population that is vulnerable to hunger and poverty.

The lessons from past and present efforts highlight the importance of a coordinated approach, blending government support with community and charitable action. Programs like SNAP and TEFAP continue to provide essential support, but local initiatives and personal donations remain vital. As we move forward, the continued evolution and support of these institutions will be essential in combating food insecurity.

Impact on Communities and Individuals

Bread lines and soup kitchens left a profound impact on both communities and individuals during the Great Depression, shaping the social fabric in ways that continue to resonate today. These institutions provided essential sustenance and served as a vital nexus of support and solidarity amidst widespread despair.

Personal stories from those who lived through the Depression highlight the deep emotional and social implications of needing to rely on these services. For many, standing in a bread line or eating at a soup kitchen was a humbling experience. As one New Yorker recounted, people often dressed up as if going to work to hide their plight, displaying the immense struggle to maintain dignity in the face of adversity.2 The sight of well-dressed individuals waiting for their share of food starkly illustrated how the economic collapse had spared no one, integrating a shared sense of vulnerability across diverse social strata.

The communal nature of soup kitchens and bread lines fostered a sense of solidarity among those affected. At Al Capone's soup kitchen in Chicago, for instance, the three daily meals served were more than just nourishment; they provided a rare moment of communal experience, where the stigmatized and isolated found empathy and companionship. Similarly, the Capuchin Services Center in Detroit became a beacon of hope, offering food and a community that shared in mutual support and understanding. People in these lines often helped each other cope, sharing their stories and comforting one another, their shared experiences creating an unspoken bond among them.

Despite the support offered by these institutions, there were significant emotional challenges. The stigma associated with receiving charity weighed heavily on many individuals, leading to feelings of shame and inadequacy. These experiences were therapeutic for some, relieving the psychological toll of their circumstances. But for many, particularly those who had once been self-reliant, the shift to depending on charitable food led to internal conflicts about identity and self-worth.

Communities, however, displayed remarkable resilience. Local responses often involved a collective effort to uplift and support one another. In Boynton Beach, for example, The Soup Kitchen became a cornerstone, not only for feeding people but for rallying the community. Volunteers, local businesses, and residents came together, donating time and resources to ensure the kitchen's success. This cooperative spirit transformed the soup kitchen into a community hub, where people could find warmth, camaraderie, and practical help beyond just meals.

The broader implications for social welfare were significant. The prominent role of religious and charitable organizations during this time laid bare the limitations of relying solely on private charity to address large-scale social crises. As communities mobilized, the glaring absence of sufficient governmental support became impossible to ignore. This catalyzed a shift in public perception, gradually leading to increased advocacy for more substantial, federally-supported social safety nets—a legacy that laid the groundwork for future welfare programs.

The emotional impact extended to children, who were uniquely vulnerable. Stories like that of a West Virginia child admitting to her teacher that she couldn't eat because it was her sister's turn painted a grim picture of intergenerational impoverishment.3 Organizations today, like Feeding America, underscore this continuing issue by reporting alarmingly high rates of food insecurity among children, reflecting the persistent challenge of eradicating hunger.

The lasting legacy of these soup kitchens and bread lines is evident in their modern counterparts. Programs like Masbia in Brooklyn, where the ambiance mimics a casual eatery, strive to preserve dignity and reduce the stigma associated with food assistance. They are not just places to receive a meal but to reclaim a measure of normalcy, reinforcing the notion that access to food is a fundamental right, not a privilege.

The legacy of bread lines and soup kitchens during the Great Depression underscores the power of community and compassion in times of crisis. These efforts fed the hungry and offered a sense of dignity and solidarity. As we continue to confront food insecurity, the lessons from this era remind us that collective action and empathy are crucial in providing support to those in need.

- Bread Lines and Soup Kitchens - June 4, 2024

- Great Depression Recovery Strategies - June 3, 2024

- Homelessness in the Great Depression - June 2, 2024